|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Return to Articles | <<< Article >>> | ||

Walton's in the Media. |

TV Guide |

|---|

|

The Long, Hard Road

To Walton's Mountain

It was all uphill even before Ralph Waite got there

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

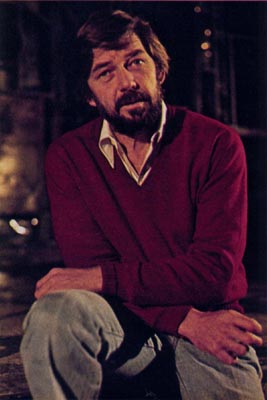

Peering from his first-row seat through tired, deeply pouched eyes, sipping coffee and chain smoking filter-tips, the director listened attentively to a procession of auditioning actors. Lights flaring from the proscenium stage silhouetted his craggy profile - a thatch of disheveled hair, a grid of forehead furrows and an unfamiliar salt-and-pepper beard and mustache, begun the day after completion of The Waltons' third season.

Ralph Waite, known to 70 million viewers as father John Walton on television's weekly celebration of old-fashioned family virtues, was utilizing the show's vacation period to immerse himself in more personal, exhilarating activity. He had allocated $50,000 of his own funds to produce and direct revivals of Arnold Wesker's "The Kitchen" and Eugene O'Neill's "The Hairy Ape" at a tiny, 176-seat theater in a shabby section of Hollywood.

"O'Neill is to The Waltons what a feast is to a nice family meal," Waite explained, justifying an enterprise that clearly aspired more to art than profit. "I began to long for a different diet, something heavier and less saccharine, because I understand life to be a lot more complex and a lot more painful than the familiar homilies echoing from Walton's Mountain." That was an understatement, considering a painful previous life that graphically paralleled aspects of suffering, intemperance, desperation and self-doubt typical of O'Neill's characters; experiences that undoubtedly contributed to Waite's haggard physical appearance. Although bright, highly educated and well-bred, he had unaccountably hit rock bottom only seven years earlier and two miles distant. Zero job prospects. Absolutely no money. Behind in his rent at a fleabag Hollywood Boulevard hotel, pleading with the remotest actor acquaintances. for 10 dollar loans.

"There's something wrong here," he was telling himself. "I am way out at sea. At 39 years of age, I can't live like this. I won't live like this. I feel like a bum. I have to get out of this business. "

The major gambles of his life - abandoning three potentially rewarding careers and entering the notoriously insecure field of acting-apparently all had failed. Frequently, in tortured self appraisal, he would reflect on what might have been and used to be. Such as 1953, the year he spent as a social case worker in New York's Westchester County, ministering to 75 needy families -often on his own time, after hours. Waite's idealism eventually collided with what he considered to be a lack of bureaucratic compassion, forcing his resignation.

"The welfare-department attitude toward the poor was condescending and racist," he observed. "it was just handout time. Nobody really cared about the people themselves."

His altruistic inclinations next brought him to the Yale School of Divinity, where he studied for three years. He was ordained a Presbyterian minister, ultimately taking over as pastor of the Garden City Community Church in suburban Long Island. "He was a top-notch minister and a dynamic actor in the pulpit even then," recalls a former parishioner, Bill Hayes, currently appearing on the TV soap opera Days of Our Lives. "But I don't think Ralph ever enjoyed being asked to conform to the mold or the stereotype expected of most clergymen. He was disturbed by people telling him to straighten his tie or shine his shoes or fix the hole in his sock. He was a very individualistic guy who wanted to be himself."

Disenchantment with religion in general increased after several local ministers reneged on promises to join him in an NAACP-sponsored picketing of a local five-and-ten-cent store whose hiring practices discriminated against minorities.

Deciding that heaven can wait, he took a year's sabbatical-"I felt much like an orphan looking for some means to find my way into the world" - before surfacing as a religious-book editor at Harper & Row in Manhattan, writing dust-jacket blurbs and handling publicity and promotion. Meanwhile, 15 years and three children after marrying his college sweetheart, Waite had separated from his family. "The big problem was my constant need to prove myself, to compete, to somehow work out my destiny," he would later learn through psychoanalysis. "I still had a compelling drive to accomplish something in the world, so I placed myself In the center of a universe that revolved around me. That was too heavy a burden for my wife to deal with."

Following a particularly doleful dinner one night in the winter of 1959, Waite tagged along to Bill Hayes' acting class to take his mind off personal problems. What he experienced was a revelation. "I think he could have switched jobs and lives right then and there," Hayes remembers. "The class seemed to work as a release for Ralph, a catharsis. His eyes were opened."

"Previously, I attempted to justify my life as worthwhile by doing what seemed to be important things, like working with other people," Waite said. "Both in my personal and professional life, I was always taking care of everybody else. That night, I began to sense that maybe there was a way - through acting - where I could do something for myself by ventilating some of my own feelings."

Several weeks later, he unburdened himself in an angry, emotional classroom reading from Tennessee Williams' one-act play "Mooney's Kid Don't Cry." "I couldn't believe how much better I felt, having finally gotten some of my feelings out," he said, evaluating his first acting attempt. "I just felt very open and alive."

At the suggestion of a classmate, Waite applied for-and won-the $25 a-week position of general understudy at the off-Broadway Circle In The Square Theatre, then presenting a hit production of Jean Genet's "The Balcony." His amateurish debut, in which he replaced the indisposed lead on eight hours' notice, was a nightmare. One shaken actress stalked off the stage, threatening to boycott the second act. Another got him through the night by prompting many of his lines.

At the end of the six-month run of "The Balcony," Waite had performed almost every role, and received such encouragement that he quit his $15,000 a-year publishing job to pursue acting full time. After bidding his Harper & Row colleagues farewell, he stood on the corner of 33rd Street and Park Avenue, thinking: "What am I gonna do for money now?"

Waite waited on tables, drove taxicabs and tended bar at actors' hangouts like Joe Allen's and Downey's for nearly four years, while studying acting, working in summer stock and occasionally landing understudy jobs. His income from acting ranged between $2000 and $4000 annually. The inability to support his family contributed to gnawing frustrations and building resentments.

"Especially in New York, where opportunities are not plentiful, the acting profession is aggressive and hostile, a ruthlessly competitive battleground," Waite declared. "Since you have to keep driving to make it, the normal instincts of generosity toward others are discouraged. Lacking constant affirmation, you don't feet important. So you compensate by getting into the typical wounded actor's ambivalent bag, yelling at life while living it to the hilt. I really got into it. This was my Irish poet period. I was a heavy liver and a heavy boozer. Unfortunately, there's no way to learn anything if you're always softening reality with a few drinks. It's an avoidance behavior., What 'liquor represents, when you get into it heavy, is arrested emotional development. That's when you stop growing."

Waite stopped drinking and gradually came to comprehend more about himself during four years of analysis. "My psychiatrist helped me get through this time of tremendous transition," he said. "One of my daughters got very sick when I started acting, and she eventually died of lingering leukemia. That, on top of my divorce and everything else, really felt like something out of O'Neill. Therapy held me together."

An important professional breakthrough finally occurred in the 1965 off-Broadway production of "Hogan's Goat," opposite Faye Dunaway. Removing his opening-night makeup, Waite returned to his bartender's job at Joe Allen's and waited for the crucial New York Times review, which one of the patrons read aloud. Hearing high praise for both the play and his performance, he jumped over the bar, removed his apron and ordered drinks for the house.

"That's it," he thought to himself. "I won't have to serve drinks for a living any more."

Waite was rarely idle in the theater after that. There were three repertory seasons with the respected Theater Company of Boston, whose members included the then-unknown Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino; the role of Claudius in a rock version of "Hamlet"; a pair of Broadway one-acts written by Tennessee Williams. The money was not spectacular, but at least he was surviving.

Then came the plum part he had been anticipating for years, the lead in "The Watering Place," a play that struck a deep emotional chord within Waite, reminding him of the relationship with his late father.

"He was a very strong and vigorous man, an athlete/hero in college, a macho, charismatic construction engineer," he explained. "He intimidated me, although I adored him. We never got along very well. We argued a lot. He never knew what to make of me. I guess I was a little too much of a sissy, too sensitive for him. Yet he was the kind of guy I wished I could have been, representing exuberance and strength. He was a heavy boozer and died young at 49, from living too hard and drinking too much."

Waite was convinced "The Watering Place" would make him a major Broadway star. When all of Sardi's stood up to applaud his post-opening entrance, which he gratefully acknowledged with a bow, he knew that he'd made it. But within an hour, the Times' critic had assailed the play, the producer closed it after only one performance and Waite had ignominiously exited from the restaurant.

"I was so destroyed that I went home and hid under the covers for two days he recalled. "I had no resources to combat this event. My whole being was called into question."

And it was then, following a visit with his former wife and children in Northern California, that Waite wound up in a Hollywood hotel room-broke, disillusioned and discouraged. He swallowed hard when circumstances forced him to lake a part he felt unworthy of an established New York stage actor-a one-day, $400 job on Bonanza, his initial television exposure.

For reasons best described as serendipity, Waite suddenly began getting hired for motion pictures: "Five Easy Pieces," playing Jack Nicholson's older brother; "The Grissom Gang"; a featured role opposite Charles Bronson in "The Stone Killer." And, most fortuitously, "The Sporting Club" -a film produced by Lee Rich, later executive producer of The Waltons.

They had not seen one another for three years when Waite appeared in Rich's Burbank Studios office, hoping to sell a cathartic screenplay he had written about the experiences of a struggling New York actor. "I took one look at him and said: 'Ralph, shave the beard, let me get in touch with your agent and come down tomorrow or the next day for testing'," Rich recalls. "He looked exactly the way I had envisioned the father of the Waltons-a man with a very powerful, sturdy face who still conveyed compassion and understanding for other people." Ten days later Waite signed a contract that this autumn - in The Waltons' fourth season - will gross $8500 weekly. His screenplay has never been produced.

"In the past two years, I've discovered there's nothing I or anybody can do about their lives," he observed, motioning to an assistant for a fresh cup of coffee. "What's gonna happen is gonna happen. My talent didn't get me the Waltons job. I just happened to be there that day. I'm just amazed as I begin to see with some clarity this random course of my life that once made no sense to me."

Waite attempted to alter his random course last spring by demanding that producer Rich either help subsidize his theater, or release him from the remaining three years of his contract within a year-so he could pursue stage acting full time. Rich insisted that Waite live up to the agreement, and filed a lawsuit after the actor boycotted the filming of two episodes. On the advice of an influential friend, Waite meekly returned to the set, failing to win either demand. He also forfeited $17,000 in salary.

Waite's recitation was interrupted by the resumption of auditions for the Oxford Theatre's next production. Parading before him was a kaleidoscope of hopeful actresses provocatively named Tara or Lisa or Kim; wearing Levi's and leotards, padded chests and plunging necklines, bare feet and Kork-Ease sandals; tentatively offering retouched photographs and Xeroxed resumes. Some had wet palms; others were supercool. They alternately preened, flounced, cooed, stammered and wiggled, trying to influence the random course of their own lives by landing a job that paid the paltry union minimum of $55 a week, but -more important- would provide a showcase of their abilities for visiting TV producers and casting directors.

"Thank you, my love," Waite invariably said, springing to his sneakered feet with paternal hugs, cheek kisses and grasps around their waists,' offering those gestures of warmth that only an actor who has been there before knows are essential to a fellow performer's psyche.

"California and The Waltons allowed me the time, the space and the money to settle down a little bit and not be so driven; to come to sort of a personal understanding with life," he said, contemplatively chewing on a matchstick. 'I had to give up a lot of my ego trip-that I was one of the great American actors destined for great things on the stage-and come to an appreciation of the fact that I'm in business, that I have to make a living and that television is giving me good work to do. The New York actor would say that I've sold out. But I can't live with that kind of arrogance any more. My whole attitude has shifted to a great deal of gratitude for simply being alive and having honest work to do. My ego is in much better shape."

But not completely at ease. Following the audition and departure of a particularly toothsome aspirant, he turned to an aide and sighed, rhetorically: "Why can't I have a beautiful woman like that?"

Someone asked why, indeed, he could not. "I'm just not very good at long term relationships," Waite shrugged. "I guess I spent too many years being protective of myself-rushing through life, trying to get something done-to learn how to love. So I feel very young in that area, very insecure. I still have this abiding feeling that nothing is going to make me secure. Not The Waltons. Not a woman. If you realize your security isn't in anything beyond your own self and your own relationship with life, it takes a long time to learn how to live it. At 46, I'm just beginning to learn how to live." |

|||

| Return to All Articles | <<< >>> | ||

|

|||||||||||

| About this Site / Links | Contact Us | FAQ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|