|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Return to Articles | <<< Article >>> | ||

Walton's in the Media. |

Unknown Source 1974 |

|---|

Earl says that the Hamners represent real family relationships

"not just rounding up the family for a cookout

but real close-family togetherness."

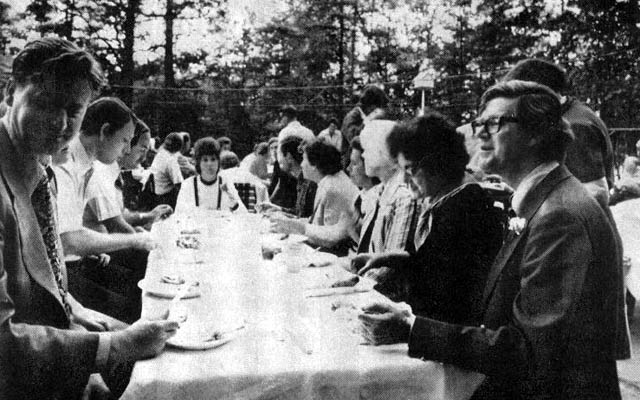

| Hamners and friends enjoy a meal together at the Schuyler, Va., home of Aunt Sis and Uncle Guilford Giannini, brother of Doris (Mother) Hamner. Held this year on May 12, the annual family celebration is - always - in honor of Uncle Guilford's birthday. Earl, author of the Walton TV series (right front), jokes with his sister, Audrey (sitting next to him) and brother, Paul (opposite). His younger sister, Nancy sits at the far end of the table. |

The Real Waltons

|

|

The game went on for several years, until Marian - the ringleader and eldest girl - pulled the string on the homemade trap prematurely and caused a fatal concussion to a redbird. That's when Mother Hamner - known to her children today as Doris - put an end to bird trapping.

This sort of thing has gone on - perhaps a little less imaginatively - in other American homes in other years.

But this particular family is very, special because it has been immortalized on television as The Waltons. Ever since a warm, nostalgic 1971 TV Christmas special called The Homecoming introduced the members of the Walton family, they have been welcomed into millions of homes every week as emissaries - of lost values and a life-style that many Americans would apparently like to rediscover.

A lot of these viewers are asking: are the Waltons real? And, if they are, can any family be that single mindedly wholesome and principled?

The answer to the first question is an emphatic "yes." The Waltons - real name, Hamners - are very real people. But the answer to the second question is a little more complicated.

John-Boy, the poet-writer-biographer of the Walton family, has performed the same function for the Hamners. Earl Hamner, Jr., a gentle, gangling, soft-spoken, perceptive, fiftyish man, has drawn on his own childhood and his own family to create a half-dozen books, a movie called Spencer's Mountain, and a television series that last year captured virtually every Emmy award in sight. Behind the characters in his books and TV's Walton family are the Hamners of Virginia: eight brothers and sisters, a mother still living, and a father - recently deceased - whose salty memory lives exuberantly in family talk and in Earl's writings.

The Hamner children, now grown, include a banker as well as a waiter on the male side, and on the female, an employment counselor who is also the mother of five children. Their names are Earl, Jr., Cliff, Marian, Audrey, Paul, Bill, Jim and Nancy. On the TV show the comparable young Waltons are John-Boy, Jason, Mary Ellen, Erin, Ben, Jim-Bob and Elizabeth. (The reason for the discrepancy in numbers is that Paul and Bill Hamner have been combined in the single TV character of Ben for budgetary and other technical reasons.) All the Hamners except Paul, who manages a shoe store in New Jersey, and Earl, Jr., who is head writer of The Waltons in California still live in Virginia, within an hour or two by car from the family home in Schuyler, where they go frequently to visit their mother. They see each other often and continue to support one another emotionally, economically and - when necessary - physically. "They are," says Marian's husband, psychologist Glenn Hawkes, "totally supportive of one another and, I suspect, always will be." (Hawkes, and all the family in-laws, are jokingly referred to by the Hamners as "outlaws.")

Doris Hamner lives alone - since the death of her husband in 1969 in the family home in Schuyler, a crossroads company town about 30 miles southeast of Charlottesville. She's a tiny, red-haired woman who looks more Irish than Italian (her parents were Gianninis, descended from craftsmen brought over from Italy by Thomas Jefferson to do the stone work at Monticello). Her gentility hides the mental toughness that enabled her to raise eight children in a five-room house during the Depression. She had the strength to preserve her own moral, spiritual convictions in spite of challenges from inside and out.

A devout Baptist all her life, Doris clung steadfastly to her church while her husband marched happily to a different tune, pointing out that the church opposed everything he favored especially dancing, drinking, card playing and fishing on Sunday. His concession to Doris on religion consisted of agreeing not to head for the river with his fishing pole until after his wife and the other good Baptists were in church. Still, many a yearning male in once-a-week coat and tie watched through church windows as Earl Hamner, Sr., marched to the river with pole and minnow bucket in hand.

The young Hamners, as a result, had some conflicts in the area of formal religion, although Grandma Giannini pointed out to them carefully that their father was "a good Christian man even if he didn't go to church." The children attended church in deference to their mother, but their spiritual affinities were more often allied with their father's. This led to an occasional confusion in roles, as - for example - the day Marian, then ten years old,came home from a communion service fired both with Baptist fervor and her father's practicality. Entering the back door, her eyes lit on a flock of chicks, newborn and flagrantly unbaptized. Marian never hesitated. To ensure that their souls might go to heaven, she fetched a bucket and started baptizing the chicks. A dozen or more had been dispatched prematurely to the Great Chicken Beyond before higher human authority stopped that ceremony.

Stories like this tumble out whenever the Hamners get together: Cliff (Jason Walton), wiry, bespectacled, talkative - a cost estimator and draftsman in Richmond, who finds his greatest pleasure in the hunting dogs he raises and the outdoor life he loves; Bill (Ben), bulldog-shouldered, reticent, a construction foreman and action man of few words who also shares his father's passion for hunting and fishing and the basics of soil and machinery; Jim (Jim-Bob), slight, gentle, introspective, the only remaining unmarried Hamner and a bank official in a small upstate Virginia town; Paul (the other half of Ben), easygoing, sensitive, thoughtful, given more to contemplation than action, running a shoe store in New Jersey; Marian (Mary Ellen), bright, brisk, outspoken, still mischievous, a Richmond housewife and mother; Audrey (Erin), dark, attractive, once intense and withdrawn, now easy and talkative, an employment counselor and mother of five in southern Virginia; Nancy (Elizabeth), the baby, spoiled by her own admission and the enthusiastic affirmation of her brothers and sisters, pretty, still searching for identity, married to a physical-education teacher who works with delinquent children in a Richmond area school. And, of course, Earl, Jr. (John-Boy), chronicler of the Hamners-Waltons, who lives in California with his wife and two teen-age children but visits home often and phones his mother every Thursday night to find out how she liked "the show."

This was -and is- a family, says Earl, Jr., today, whose members "always knew where we came from and who our people had been for many generations, with the sense of belonging that goes along with that knowledge - and with being a Virginian."

Both Doris Giannini and Earl Hamner, Sr., were brought to Schuyler as infants when their fathers came to work in the soapstone quarry. The role of Grandpa in The Waltons is a composite. Neither grandfather ever lived with the Earl Hamner family. Grandfather Hamner died almost 40 years ago, and his wife moved to Richmond, where she opened her home to her grandchildren until she died at the age of 94. The Gianninis lived out their lives in Schuyler, providing a second home for the Hamner children until all except Jim and Nancy were raised and gone.

Although most of the Hamner children grew up during the Depression years, there was never any sense of deprivation a point which TV viewers today find hard to understand. Earl, Sr., was a skilled machinist who, was never out of work very long, When he was laid off at the quarry, he found work in nearby Waynesboro which required him to travel several hours a day to and from his job. (The Homecoming was a composite of several incidents during this period.)

To save money and expedite travel, Earl bought a secondhand motorcycle that never worked very satisfactorily. After one particularly bad week, he spent all day Saturday fixing the motorcycle. Sunday morning he took it out for a road test. It promptly balked and threw him over the handlebars. Without hesitation, Earl wheeled his cycle to the nearest abandoned quarry, gunned the engine and watched with satisfaction as it plummeted over the edge and disappeared in the deep water. Then Earl quit his job in Waynesboro and cut and sold wood until he got back his job at the stone quarry. "We weren't poverty stricken," says his eldest son today. "We simply had an absence of money - and, therefore, of things you have to buy at the store with cash, things we couldn't provide at home."

Earl, Sr., moved through this period blithely, doing his own things in his own way. He was an expert fisherman and hunter and always kept game on the table. He was jealous of this preserve and adroit at protecting it. When he discovered a hill that was especially rich with game, he scared off fellow hunters in Schuyler by telling them he'd stumbled on a huge snake there that had apparently escaped from a visiting circus-and was still on theloose. As a result, Earl had the hill all to himself as long as he wanted it. He was a magician with tools, creating baseball bats for the kids on his lathe (Grandma Giannini provided the balls by sewing a covering over a walnut wrapped with layers of string).

The children necessarily made their own entertainment, and it sometimes got rather exotic. There was, for example, the muggy summer day that ten-year-old Bill saw the family hog sweating feverishly and in a fit of compassion decided to relieve him. Bill made a large pitcher of ice water which he dumped on the hog's head and back. The hog died and the family blamed Bill's shock treatment. Doris refused to butcher the animal because it hadn't been bled properly. "Dad was pretty sore," recalls Bill, "but the only punishment I got was having to dig a hole deep enough to bury that hog."

Throughout such activities, there was a remarkable family bond. Earl, six years the eldest, was bookish and a little mysterious, and, so became a hero and mentor to the other children, even when he would rather have resigned that role. "Wherever I went," he remembers, "they would trot along behind. I tried to lock them out or run away from them, but it never worked." But these were only minor difficulties that scarcely rippled the surface of family solidarity. "When new babies came into this home," says Doris, "there was no resentment. Every child was made to feel wanted and welcome, and it was." The Hamners were - and are a demonstrative family which find no embarrassment in touching. Men embrace one another, and the children kissed their father up to the day he died.

Within the Hamner household there was an absolute division of authority that was seldom challenged. Inside, Doris ran the show, while the outside was Earl, Sr.'s domain. Earl, for example, enjoyed a drink, an appetite that rankled Doris' Baptist instincts. So, throughout their life together, Earl did his drinking outside the house.

"He would test Mother every once in a while," recalls Cliff, "by bringing a bottle into the house. She'd find it and pour it down the drain, and he'd never say anything'. Just wait a while and try her again."

Because the children spent much of their time around the house, Doris was generally the disciplinarian. Only rarely did she ask her husband to execute a sentence she had passed down. "I dealt with them," she remembers. "I didn't expect Earl to do it when he got home." The ultimate Doris punishment was a switching, and the ultimate adolescent agony was having to cut from the peach tree in the back yard the switch that delivered the punishment.

The only time Marian can remember corporal punishment from her father was when - with a vocal assist from Cliff in the background - she sawed a prized limb off the hated peach tree. "He had such respect," says Marian, "for a tree or even a seed. I can always remember him holding out his hand with three seeds in it to try to explain life and death to me. He said these seeds seemed to be dead, but if I put them in the ground and cared for them, they would grow up and become trees. I suppose that's why I expect to come back some day as a dogwood tree, which is the most beautiful thing I know."

The only time any of the children can remember a direct confrontation between their parents that overlapped lines of authority was the matter of Bill's curls. It's hard to imagine today, but the barrel-chested, rugged Bill was blessed as a child with a remarkable set of red curls which Doris loved. So she let them grow. Earl growled about it from a distance until Bill was three years old. Then, pushed to his outer limits, he told Doris, "Either put a dress on him or cut his hair. Today." The hair was cut.

Doris still sounds chastened 30 years later when she tells this story. "Earl," she says a little resignedly, "was very proud of his boys."

With a family of ten in the restricted space in which the Hamners lived, there had to be rules. They were few, simple and direct. Girls didn't go out alone with boys until they were 16 years old. Whenever a Hamner child left the immediate environs of the yard, he told someone in authority where he was going and about when he'd be back. Everyone made his own bed and household chores were assigned - and performed - with minimal argument. That was about it. Outside these rules there was a remarkable kind of permissiveness possible only in people who really love children. "We had our own time," remembers Audrey, "and we nagged at during that time."

The rules were administered by Doris, and she was admittedly overprotective at times. Water, for example, frightened her because of the death by drowning of two relatives, and she kept the children away from swimming holes. Consequently, most of them still don't know how to swim. Their mother's concern was also partly responsible for the aggressive and almost unquestioning way the Hamner children looked out for one another. Earl, Jr.'s gentle manner ("I've seen him," says Cliff, "deliberately miss birds or animals he had a direct bead on when we went hunting. He liked the outdoors, but he could never bring himself to kill anything") generally kept him out of adolescent trouble, but the rest of the clan was constantly in and out of fights. And whenever a Hamner was hassled ("even if he got into it through his own stupidity," recalls Cliff), any other handy member of the family plunged in to help. Sighs Nancy, who was never permitted to forget that she was the baby: "They always protected me so much that I never learned how to do anything for myself."

The home surroundings - which, except for enlargement of the kitchen, are much the same today as they were when the children were small - were, at best, modest. The kitchen, a tiny living room, bathroom and the parents' bedroom were downstairs, and upstairs two bedrooms served as male and female dormitories. Hot water for the single bathroom came from a small, wood-burning heater which took forever to heat up a tubful of water. Babies slept in the parents bedroom until they were old enough to move upstairs, where only Jim - by an accident of chronology - was blessed with a single bed. All meals were taken in the kitchen at a picnic table with benches on either side and chairs at the end for Doris and Earl. Positions on the benches were fixed by seniority and never changed.

With inside space restricted, the Hamner children did much of their growing up out-of-doors. The front porch, which spanned the house was always occupied. Front and back yards were fenced and deep. The front yard offered the excitement of the road, while the back yard ended in Earl's barn and the pens for whatever animals the Hamners were boarding at the time. Doris' sister lived next door, her parents down the road, the Baptist church was just over the hill, and the school was across the street.

Education was important to the Hamner parents, and Earl, Sr., once told his boys they would have to go to school until they could whip him - an eventuality both unthinkable and impossible. "Father," remembers Jim, "was hell-bent and determined that we would graduate from high school, and each Hamner kid helped each succeeding one. That continued right into college, when we would all kick in to send spending money to the current one in college." Six of the Hamners got to college this way - with a powerful assist from their grandmother in Richmond and from older brother Earl after he began selling radio and TV scripts in New York.

Earl's first big success came in 1961 when Spencer's Mountain was made into a motion picture in which Henry Fonda and Maureen O'Hara played the elder Hamners. Earl and Doris came proudly to New York for the premiere, taking it all very much in stride. When the picture opened in Richmond a few, days later, Cliff's small daughter was so distraught when she saw a tree fall on her grandfather that Cliff had to get Earl, Sr., on the phone to convince the little girl he was all right.

The Hamner life-style changed very little after this triumph. There was a growing covey of grandchildren to command attention and Jim and Nancy were still at home. This caused logistical problems when the clan came to visit, but Doris always insisted they stay in the family homestead. Audrey remembers her father once getting up at midnight and telling a group still talking in the living room that he'd had his sleep and someone else could now have his bed. He had once told Marian that if she didn't capture a husband soon, he was going to raffle her. And when Nancy turned 25, she remembers ruefully, her father told her that he was not only going to raffle her but intended to give away the chances. (The ploy must have been effective since both girls got married soon afterward.)

Earl, Sr., never saw The Homecoming. His son was just beginning to write it when the head of the Hamner clan sat up abruptly in bed at two o'clock one morning and said to his wife, "I'm dying" - and did, from a heart attack. "He died in great style," says Marian, " - just the way he lived."

Since then, Doris has lived on steadfastly in Schuyler, terribly lonely at first in spite of the family around her. (There are presently 32 Hamners - including "outlaws" - and 15 grandchildren.) Now the loneliness has eased a bit, because of the hundreds of new friends who stop almost daily in Schuyler to visit Doris - people with license plates from Louisiana and Iowa and Maine have inquired at the Chamber of Commerce in Charlottesville or the general store in Schuyler for directions to "the Walton place." They find their way to swap kinfolk talk with Doris or tell her how much they enjoy the show and wish its values might be transplanted to their own family life.

Why this potent and growing fascination with the Waltons?

Says Earl, Jr.: "I think people are hungry for a sense of security, and the Waltons represent that. They're hungry, too, for real family relationships - not just rounding up the family for a cookout, but real togetherness where people are relating honestly." Have these values been carried on to the next generation of Walton-Hamners?

Says Marian: "Parents deal with different kinds of problems today. When I was growing up, the people who had any sort of influence on me felt pretty much the same way as my parents did. Today, many other people influence the lives of our children' outside the immediate family, and I don't think our parents faced this problem. Even so, the things our parents instilled in us run deep and they have filtered through us to our children - a little confused, maybe, but there. Sometimes, though, it seems to me that we and other parents of our generation have had almost a reversal of roles - now the parents are striving to please the children instead of the other way around, I'm guilty as anybody, and I don't especially like it."

Says Audrey: "I have five children and I've tried to teach them the same basic values we lived by when we were growing up. And at least I have a good idea of where they are and what they're doing."

Concludes Earl: "Some of what may seem today to be parental indulgence is a new kind of respect for young people - and maybe we kept rights from children for too long. Still, I would hate to see the values by which we lived as children watered down too much because they are values that can keep a people strong."

A few weeks ago, among hundreds of letters she now receives every month, Doris Hamner read a pathetic little note from a boy in the Midwest who wrote wistfully: "My home life is so different from yours. We don't talk to each other very much. I wish I could have lived in your house."

"Maybe," says Doris, "it comes back to the Golden Rule. How often we told that to our children and tried to apply it in our dealings with each other and with people outside the family. If we could really 'do unto others as we would have them do unto us' maybe we wouldn't need any other rules. At least that's the way it worked in our household."

|

|

| Return to All Articles | <<< >>> |

|---|---|

|

|||||||||||

| About this Site / Links | Contact Us | FAQ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|